At this point in my career across the biotech-related projects I’ve run, I’ve personally raised about $100 million. In some ways this feels like a lot, but given the scope of biotech and hard tech projects I care most about, it’s really just a drop in the bucket. From these experiences though, I’ve learned some things that I believe can help other founders navigate fundraising, and want to share them – especially for newer founders working on interesting technologies that may be approaching fundraising for the first time.

Most of what I am saying is for biotech, but I think a lot of the observations apply for medical devices and other hard science startup fundraising too.

Understanding Today’s Funding Landscape

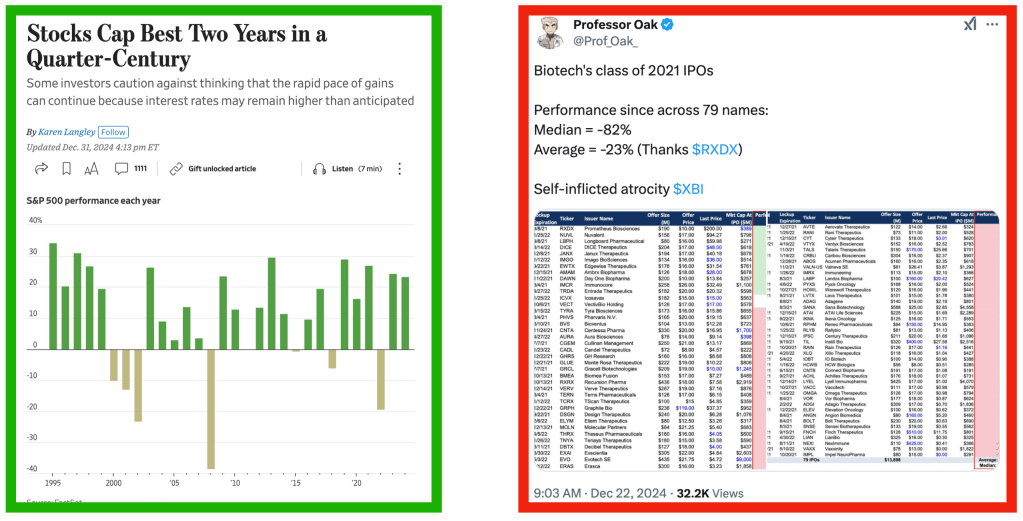

Biotech exists in a unique corner of the investment world, one where the promise of revolutionary breakthroughs meets harsh realities of extended development timelines and significant capital requirements. This is truer today than ever – while the broader equity markets has seen unprecedented growth over the past two years, the biotech sector has remained in a relatively depressed state.

The stark reality is that bringing a new drug to market typically requires hundreds of millions, if not over a billion dollars, with development timelines stretching 10-15 years. About 90% of drug candidates fail during development, and of those that do succeed in reaching approval, only about 5% achieve blockbuster status with over $1 billion in annual sales. These are the fundamental challenges that shape how many investors think about the industry.

That is all true in good times, but the reality is that things right now are in an even weirder place; the COVID years created an interesting aberration. During 2021, we saw a surge in biotech investment driven by a perfect storm of conditions: historically low interest rates, increased attention on biological threats, and inordinate worldwide attention on mRNA vaccine technology. This period of enthusiasm led to significant funding for many companies that, in retrospect, might not have been ready for the spotlight. The median biotech IPO from 2021 is now down 82%, a sobering reminder of how quickly market sentiment can shift.

The Pool of Investors is Changing

While that’s all daunting and makes it harder in many ways for biotech founders to succeed, on the good news side, the investment landscape has diversified. Historically, most venture funding came from traditional biotech VCs who operated with a specific playbook: take large ownership stakes upfront and often bring in professional managers early, relegating scientific founders to advisory roles. While this model has certainly produced successes, it’s not the only way to build a biotech company – and increasingly, it might not be the best way.

Having investors control the companies can lead to perverse shorter-term oriented incentives, poorer management with thinking about things ‘top down’ with split focus across many companies, greater conservatism on risk-taking (ie more companies working on fairly derivative aims), and less maintenance of holding technology development and translation as the north star of the purpose of startups in the first place.

Because of examples of great success in the broader technology world, we’re seeing the emergence of what I’d call a more “Silicon Valley” mindset in biotech investing. This approach prizes technology development at the core of the company’s DNA and – drawing from examples in tech such as Microsoft and Meta and in biotech such as Regeneron and Genentech – recognizes that technical founders who can grow into business leaders often build more innovative and ultimately more successful companies. This shift has opened up new avenues for fundraising that founders should understand and look towards.

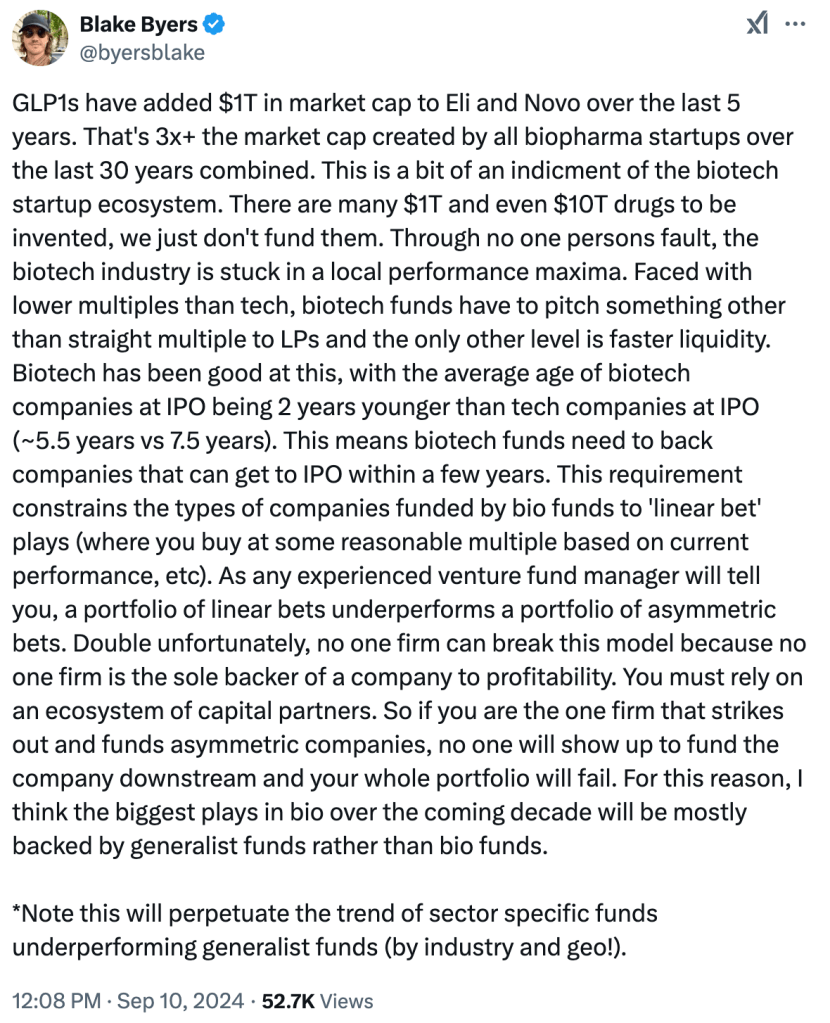

Today, there are effectively three new categories of investors emerging alongside traditional biotech VCs. First, we have large generalist funds that have amassed billions in capital and are increasingly interested in biotech’s massive potential. These funds bring a technology-agnostic approach and often have a higher tolerance for risk and long-term vision (see tweet above for a perspective on how these funds might redefine things).

Second, we’re seeing specialist boutique funds (like my fund, SciFounders) that specifically focus on founder-led biotech companies. These funds often provide more flexible terms and deeper support for technical founders transitioning into business leadership roles – I personally think these funds will play a big part in helping scaffold great companies at the early stages of company formation in the coming decade.

The third category is perhaps the most unique: high-net-worth individuals, often successful entrepreneurs from the software world, who want to deploy their capital toward meaningful technological advancement, or may personally care about eg the disease you’re trying to address. While these investors can be harder to access, they often prove to be excellent partners due to their patient approach and alignment with long-term technology development. I have funded my company Conception to great degree with backing from folks like these, and they have thus far been excellent partners that are mission-aligned and helpful – they deeply understand the founder experience.

Telling a Story that Stands Out

Having multiple potential sources of capital is encouraging, but it doesn’t change the fundamental challenge of the current environment: the bar for funding has become higher, and you need to stand out. This is where effective storytelling becomes crucial, though perhaps not in the way many founders initially think about it.

The most compelling biotech stories aren’t about making your technology sound more complex or impressive – quite the opposite. Your challenge is to make something genuinely revolutionary accessible to an audience ranging from someone who might have only taken high school biology to someone that may be extremely technical. This isn’t about dumbing down your science for the former; it’s about crystallizing its essence and potential impact to be communicable to all.

I’ve seen many brilliant scientists struggle with this balance. They either dive too deep into the technical details, losing a huge portion of their audience, or stay too high-level, failing to convey why their approach is truly differentiated. The sweet spot lies in being able to tell your story in layers. Your initial pitch should be clear enough that anyone can grasp the potential impact, but you should be ready to dive deep into technical specifics when questions arise. Think of it as having multiple gears in your presentation style – you need to be able to shift smoothly between them based on your audience’s engagement and expertise.

Before you even begin crafting your story, you need to be brutally honest with yourself about whether what you’re working on is truly differentiated. This requires a deep understanding of what academic labs, other startups, and larger companies are already pursuing; it’s a big ding if you don’t know the competitive landscape well enough to know if your idea is differentiated.

To illustrate the investor perspective a bit better based on firsthand experience– my fund talks to about a dozen companies per week, and most of them honestly seem like repeat ideas of what our team has already seen (for example, we’ve seen countless CAR T companies, or generic cellular agriculture companies that bleed together). Ideas also have to feel big beyond feeling unique and special – most investors want to invest in things that they can believe can be multi-billion dollar companies if they are truly grand slams. Small ideas are harder to get excited about, especially when risk factors in hard science/biotech company building are so high for most if not everyone.

If your approach feels derivative (or actually is derivative) without a clear explanation of why it could be significantly better, you’ll likely struggle. You need to articulate clearly why your approach is fundamentally different or why timing and circumstances are now more favorable. And if similar companies are struggling with technological progress or fundraising – or if they seem to have a similar technology well under their control – that’s often a hurdle for investors to develop conviction too.

Running an Effective Fundraising Process

Fundraising requires a delicate balance of urgency and patience. You need to maintain momentum while giving investors enough time to conduct their diligence. One approach I’ve found effective is maintaining a light sense of paranoia about how you’re performing, and maintaining that until the process is fully finished (ie money wired from investors). Remember, investors are looking for reasons to say no – it’s your job to systematically eliminate those reasons before concerns have a chance to manifest.

This means being incredibly responsive to investor queries, often turning around answers within hours rather than days. It means following up politely but persistently with investors who go quiet- I personally most commonly do on a weekly basis for a couple pings, unless I’m trying to time something else for more momentum. And it means running a coordinated process where you’re talking to multiple potential investors simultaneously, creating a sense of momentum and, ideally, competitive tension.

Make a prospect list of 30 or even 100 investors that you think could be a fit for what you’re working on based off their existing portfolios and interests. It can be a good idea to select a subgroup of these to trial run your pitch and collect feedback, before jumping into reaching out to all of them at once. Warm introductions are better than cold reach out, but don’t be afraid of cold reach out either – I have found cold reach outs personally to be be incredibly effective paired with a thoughtful and concise note.

If you run a good process and your technology is truly compelling, you’ll hopefully find yourself with multiple investment offers. At this point it becomes about choosing the right partners. Taking on investors is often described as “getting married” – these are relationships that will likely last many years and through numerous challenges.

The traditional advice is to optimize for the highest valuation or the highest dollar amount, but this can be shortsighted. Instead, focus on finding investors who share your vision for the company, have the patience to see it through, and are going to be easy to get along with. I emphasize the last point, as investors that are a pain (especially if on the board or having significant control) and significantly harm the trajectory of the company. This means carefully evaluating the character and track record of your potential investors – and not just the firm, but the individual partner you will actually be dealing with.

Most good investors at the early stages of a company will probably be fairly benign, and honestly of limited help – especially for science heavy companies, it’s unlikely your investors will be able to help deeply with eg major R&D work that you will be most consumed with early on. Investors at large funds might see an early investment as more of a ‘call option’ for the future too, rather than something they can spend a lot of their limited bandwidth on actually helping — some partners within a firm might have background politics for their fund they need to think about as well, which you may not be privy too as well (think timing in fund cycle, their own personal investment track records, etc). That said, there are some that can be helpful (with my bias like to think we fit this with SciFounders, given we’re going through the firsthand experience of building similar companies too). If you have the option for folks like these, great- try to partner with them when you can.

Most investment deals will either be done on a SAFE note or a priced round. Early on, a SAFE note is probably a better thing to use because they can be done and investors and be closed asynchronously. Priced rounds on the other hand are much more intensive and custom in deal terms, racking up tens of thousands in legal fees and potentially taking 1-2 months to close.

When it comes to dilution, I generally advise founders to target selling between 10% to at most 30% of the company in early rounds (if raising on a SAFE, determined based off the ‘post-money cap’). This range gives you enough capital to make meaningful progress while hopefully maintaining significant ownership and control of your company’s destiny. While you’ll often hear stories of biotech companies raising massive amounts at the start, these are typically either from experienced entrepreneurs or represent the “old guard” way of investing where founders give up significant control early on.

Often early on, a better approach to fundraising is what I call “hill climbing” – raising smaller amounts of capital with less dilution to meet specific milestones, then raising more funding as you demonstrate progress. This approach requires careful planning and excellent capital efficiency, but it can result in better outcomes for founders in the long run in terms of dilution, founder control, and ease of fundraising. In many cases to get initial capital in, it often opens up a winder set of conversation potentials too since there are more investors out there that can write smaller checks as well as you start out.

Be prepared too that fundraising may take a long time — things might happen fast, but some successful fundraises can take 6 months or more. And if you’re gearing up for a follow-on fundraise, try to time it to be in a position of strength, having plenty of runway — when you’re down to just a few months (or weeks) of runway remaining, you can look like a wounded animal and be less attractive to potential investors.

Managing Investor Relationships

Once you’ve secured investment, a new task emerges: managing your investors effectively. This isn’t one-size-fits-all; different investors require different levels of engagement. Some will be largely hands-off, checking in only when you reach out. Others, particularly those who take board seats, will want to be deeply involved in key decisions and strategic planning.

For early-stage companies, I generally advocate for lighter-touch investor relationships. You need to focus on building and executing rather than managing endless investor communications. That said, keeping major investors informed of both positive and negative developments is crucial. They can often be helpful in unexpected ways, but only if they know what’s happening.

The format and frequency of these updates can vary. Some founders swear by monthly investor updates, while others prefer quarterly communications. I don’t have a strong opinion on the perfect cadence – what matters more is the substance of your communications. With R&D-focused companies, especially in early stages, meaningful developments often don’t happen on a neat monthly schedule. Focus on communicating when you have something substantial to share, whether it’s progress, setbacks, or strategic decisions that need input – increase frequency in anticipation of timing for additional financing as well, so you aren’t kicking off your next process going in cold.

Funding Options Beyond Traditional Equity Investment

While equity investment is typically the primary funding source for biotech startups, there are other avenues worth exploring. Government grants and private philanthropic funding can provide non-dilutive capital, and strategic partnerships can offer both funding and validation. However, these opportunities come with their own challenges and trade-offs.

Grants can be particularly appealing because they don’t dilute your ownership. However, I’ve seen many founders fall into a “grant trap” – spending enormous amounts of time writing applications for relatively small amounts of money. Be strategic about which grants you pursue. Focus on ones that align closely with work you’re already planning to do (some may require side projects that lead you astray), and be realistic about the opportunity cost of the application process.

Strategic partnerships can be even more complex. While they can provide significant capital and valuable validation for future traditional investment rounds, these deals often take much longer to close than you might expect – sometimes years. They can also come with strings attached that limit your future options.

If you do pursue partnerships, try to run a competitive process with multiple potential partners, just as you would with investors. And be very careful about partnering away your main program – companies rarely achieve significant scale based on small royalty agreements from partnered programs. Many of the larger firms have strategic investment arms as well that operate more like traditional VCs, and these might be a different/(somewhat)faster route to engage with these kinds of companies as well in a way that still adds fundraising value.

Final Thoughts

Success in biotech fundraising isn’t a matter of just luck – it’s about striving to build something genuinely innovative, communicating it effectively, and executing with focus and discipline. The bar may be higher than ever to show you have real potential, but for high-aptitude founders working on truly promising technologies, funding is still very much available.

Remember that the biotech funding landscape continues to evolve. While the current environment is challenging, it will at points improve and at points possibly get worse. Continue to pay attention to everything going on – be it through news sources or following the right folks on social media to stay abreast of funding market developments.

And don’t hesitate to reach out to other founders and investors who have gone through this process for individual advice (including me at mattkrisiloff@gmail.com). I’ve mostly found effective people to be generous with their time when I’ve approached them efficiently with a clear ask, and shortcutting learning through others’ experiences has definitely for me been a powerful thing.